Listening to President Obama’s Inaugural Address with the variable sound quality on the Mall, I thought it was okay. An inaugural address should be more high principle and values than policy specifics and argumentation. Does the President know that he has a State of the Union Address in like 20 days? Save all of the detail and proposals and the laundry lists for then. And there was a too much of the boilerplate political rhetoric about our children and the future and freedom, et cetera.

But on a second listening, the rhetoric remains a little too detailed, but the overarching structure of the Address stands out to me, and within their context, a few lines become brilliant. The Address is constructed as a meditation on Emanuel Leutze’s 1851 painting, Washington Crossing the Delaware (above; higher resolution version here).

As SLOG’s reporter onsite Christopher Frizzelle points out (“A Review of the Speech from the Third Row,” 20 January 2009), the Address is bookended by images of storms and ice. The new President starts by saying,

The words [of the oath] have been spoken during rising tides of prosperity and the still waters of peace. Yet, every so often the oath is taken amidst gathering clouds and raging storms.

And ends with similar imagry:

… in this winter of our hardship … let us brave once more the icy currents, and endure what storms may come

Mr. Frizzelle characterizes it thus:

He is doing there what poets, namely the Romantic poets, used to do better than anyone — expressing the emotional / psychological plane of reality in terms of weather, pastoral phenomena, landscape.

The coda of the speech, the closing invocation of ice and storms, is a description of one of the darker moments during the Revolutionary War. In July of 1776 the British had landed on Staten Island and for the remainder of the year dealt a string of defeats to the Continental Army, capturing New York City, driving the Continental Army into retreat up Manhattan, across New Jersey and across the Delaware river into Pennsylvania. Washington’s army had been reduced from 19,000 to 5,000 and the Continental Congress abandoned Philadelphia anticipating British capture when the campaign season resumed in spring. It was, as President Obama described it, “a moment when the outcome of our revolution was most in doubt.”

The Continental Army encamped at McKonkey’s Ferry, Pennsylvania where General George Washington plotted a surprise attack back across the Delaware River. It was an especially unconventional move as the British had assumed the campaigning season over and established winter quarters. As President Obama relates, prior to the Christmas night crossing of the Delaware River General Washington ordered that a reading be made amidst the soldiers. The words are not General Washington’s, but those of Thomas Paine. Mr. Paine had been traveling with the Continental Army and his pamphlet, The American Crisis had just been published. It was this from that General Washington judged that the night’s inspiration would be drawn. The line that President Obama quoted from Paine is this:

Let it be told to the future world that in the depth of winter, when nothing but hope and virtue could survive, that the city and the country, alarmed at one common danger, came forth to meet it.

The victory won at the Battle of Trenton resulted in a turn away from the flagging morale of the Continental Army. When the British attempted to retake Trenton on 3 January 1777, they were outmaneuvered and quite nearly driven out of New Jersey.

The central arc of President Obama’s speech, set between the two snows and storms, reflects Thomas Paine’s image of “the depth of winter, when nothing but hope and virtue could survive.” Since it’s Barack Obama, the hope part goes without saying at this point, no? So the body of the speech addresses itself to the virtues by which the country will meet our “common danger.” Here I would like to make a list of examples, but the surprising thing about rereading this speech is how his description of the various virtues defies a simple list. They are often painted in contrasts, or without directly saying their name. I think something like constancy is a good example. “We are the keepers of this legacy.” “… the fallen heroes who lie in Arlington whisper through the ages.” For an obvious example, he says,

Our challenges may be new, the instruments with which we meet them may be new, but those values upon which our success depends, honesty and hard work, courage and fair play, tolerance and curiosity, loyalty and patriotism — these things are old.

Even when listing other values, constancy — “these things are old” — underlies them all. One of the best parts of the speech for me, especially as a leftist, was the President’s paean to workers, especially “men and women obscure in their labor.”

Among all these virtues, one receives particular recognition: unity, self-sacrifice, the common good, the gaze toward something greater than one’s self. “[Our predecessors] saw America as bigger than the sum of our individual ambitions; greater than all the differences of birth or wealth or faction.” “We will build the roads and bridges, the electric grids and digital lines that feed our commerce and bind us together.” The cynics have forgotten “… what free men and women can achieve when imagination is joined to common purpose …” “… more united, we cannot help but believe … that the lines of tribe shall soon dissolve …”

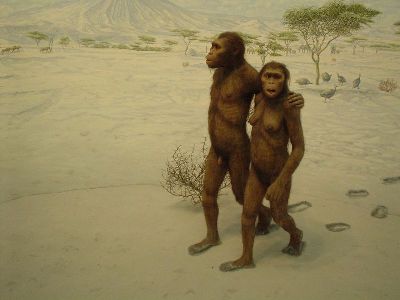

Look again now at Mr. Leutze’s painting. It’s most outstanding characteristics are an imposing river of ice between the Continental Army and the New Jersey shore, a tumult of citizen soldiers raging in boats and on the near shore. In the midst of this chaos and struggle rises the figure of General Washington, unperturbed, resolute, beyond the fray, his face fixed on distant goals and illuminated by the bursting sky.

Then study the crew of the boat. It is a microcosm of the colonies. The two oarsmen in the bow of the boat are a Scotch (note the Scottish bonnet) and an African American. There are two farmers in broad-brimmed hats toward the back. The man at the stern of the boat is quite possibly a Native American (note the satchel). There is an androgynous rower in red who is perhaps supposed to be suggestive of women. “… our patchwork heritage is our strength.”

Return now to President Obama’s Address. In this winter of adversity what persists are our virtues, above all unity. The icy currents of the bookends of the speech are the Delaware River, the middle arc of the virtues of the nation are the boat with its diverse crew of rebel irregulars. And consider the last line of the Address, “… with eyes fixed on the horizon and God’s grace upon us, we carried forth that great gift of freedom and delivered it safely to future generations.” It is a description of General Washington, father and symbol of the nation, rising out of the clamor of peoples — out of many, one — illuminated, gazing toward the future of freedom safely delivered over to the other side.

I’m not exactly a nationalist or a collectivist. I’m not so hot on all the unity talk. I more prefer an individualist, contending interest groups theory of politics. We are most markedly not one people and to say otherwise is the propaganda of an agenda. But if you dig Romanticist nationalism, then President Obama in his Inaugural Address is your artist-president, poet-in-chief.