When people think of postmodernism in philosophy, they usually have in mind a pretty specific list of thinkers such as Claude Lévi-Strauss, Jacques Lacan, Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, Jean-François Lyotard and a number of lesser lights among the French post-structuralists. But I am thinking of an alternate trajectory where the key figures would be Oswald Spengler and Martin Heidegger (Heidegger is at least a bridge figure in any version of postmodernism). In the grand historical narrative spun by these two, there is a founding period of the Western intellectual tradition where a series of conceptualizations dramatically circumscribed the realm of possible future development, determined the course of the developments that would occur and cut us off from other potential futures. For Heidegger it was the impressing of ουσια with the form of λογος in the metaphysics of Aristotle. The remainder of the Western tradition has unfolded within the confines of this original conception.

A point made by Spengler in The Decline of the West but similarly prominently by Harold Bloom in The Anxiety of Influence is that such an original conceptualization has only a limited potential. It is a potential of sufficient abundance as to play out over the course of millennia. Nevertheless, some time in the midst of the Long Nineteenth Century the Western tradition hit its pinnacle and has now entered, in Spengler’s terms, the autumn of its life. Either at some point in the recent past, or at some point in the imminent future the West will have exhausted itself. The parlor game is in arguing for various watershed events: the death of god, the First World War, “on or about December 1910” (Virgina Woolf).

In its negative mode, postmodernism is that attempt to clear away the debris of the wreckage of the West (Heidegger’s Destruktion or Abbau, Derrida’s deconstruction). In its affirmative mode, it is the attempt to get behind that original conceptualization, revisit that original openness to that unbounded potentiality of ουσια and to refound the Western intellectual tradition — or something more cosmopolitan still — on that basis. Hence the interest in Heidegger with the pre-Socratics, with Parmenides and Heraclitus.

I have lived in sympathy with similar such ideas for some time now in that my trajectory out of natural science into philosophy started with my first encounter with Thomas Kuhn in the May 1991 issue of Scientific American (Horgan, John, “Profile: Reluctant Revolutionary“). In Kuhn I was introduced to the notion of a domain formed by an original act of genus insight (a paradigm), but with only a limited potential, eventually to be exhausted and superseded by subsequent reconceptualization of the field.

I suspect that one of the causes of the structure of scientific inquiry as Kuhn describes is that the object of scientific inquiry is, at least phenomenologically, a moving target. A theory is derived within a certain horizon of experience, but just as quickly as a theory is promulgated, human experience moves on. The scope of human experience expands as our capabilities — for perception, for measure, for experiencing extremes of the natural world — increase. Consider that when Albert Einstein published the special and general theories of relativity people had no idea that stars were clumped into galaxies. They thought that the milky way was just one slightly more dense region of stars in a universe that consisted of an essentially homogenous, endless expanse of stars. They had identified some unusual, diffuse light patches that were referred to as nebula, but they had not realized that these nebulae were each entire galaxies of their own, tremendously distant, and that the local cluster striping our sky was the galaxy containing our sun, as viewed from the inside. And no one realized that the universe was expanding. They imagined that the spread of starts was static. Einstein — in what he later called the greatest error of his professional life — contrived his equations of relativity to so predict a static universe, whereas they had originally predicted one either expanding or contracting.

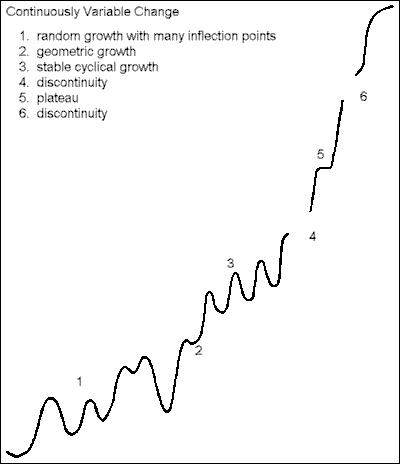

Notice that if one were to accept these ideas above, the intellectual scheme with which we would be faced would be one of cycles within cycles of superior and subordinate ideas, e.g. the Newtonian and Einsteinian and quantum mechanical scientific revolutions all take place within the horizon of ουσια qua λογος.

This is a romantic series of ideas, that a primordial act of genius is capable of radically redirecting the course of history. Of course postmodernists reject such totalizing abstractions as “Western civilization,” “the Western intellectual tradition,” and “the West” as well as the practice of constructing such grand historical narratives as the one I have sketched above. But there it is. I think that postmodernist thought is riddled with tensions, especially between its macro structure and micro tactics.