Someone at some point should drive home to the right that Iraq and Vietnam are not some apparition or anomaly requiring exceptional explanation — namely the Dolchstoßlegende — but in fact the historical trend.

Our historical-materialist problems in Iraq are multifaceted. Iraq is a combination of two pernicious trends: one relating to civil wars and one relating to asymmetric conflict.

First, on the issue of civil wars, they are by nature long, intractable and fought to the bitter, bloody end. The Los Angeles Times had the good sense to have Barbara F. Walter, author of the study, Committing to Peace: The Successful Settlement of Civil Wars (2002), write a brief summary of her survey of civil wars and the likely meaning for Iraq (Walter, Barbara F., “You Can’t Win With Civil Wars,” Los Angeles Times, 2 October 2007):

The approximately 125 civil wars — conflicts involving a government and rebels that produce at least 1,000 battle deaths — since 1945 tell us several things: The civil war in Iraq will drag on for many more years; it will end in a decisive victory for either the Shiites or the Sunnis, not in a compromise settlement; and the weaker side will never sign a settlement or lay down its arms because it has no way to enforce the terms.

Civil wars don’t end quickly. The average length of all civil wars since 1945 is 10 years. Conflicts in Burma, Angola, India, the Philippines, Chad and Colombia have lasted more than 30 years. Wars in Afghanistan, Cambodia, Lebanon, Sudan and Peru have lasted more than 15 years. Even Iraq’s previous civil war, fought against the Kurds, lasted 14 years.

This suggests that, historically speaking, Iraq’s current civil war could be in its early stages, with nothing to suggest that it will be a short, easy war.

Another lesson from history is that the greater the number of factions involved in a civil war, the longer it is likely to persist. Iraq simply has too many factions, with too much outside support, to come to a compromise settlement now. Not only is there no Shiite or Sunni who can speak for all of his side’s factions, but the parliament seems incapable of stopping the violence between these groups.

…

Civil wars rarely end in negotiated settlements. In research for a book on the topic, I found that 76% of civil wars between 1945 and 2005 ended only after one side had defeated all others. Only 24% ended in some form of negotiated solution. This suggests that the war in Iraq will not end at the bargaining table but on the battlefield.

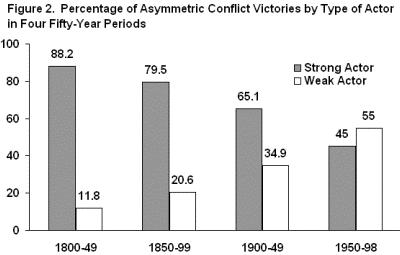

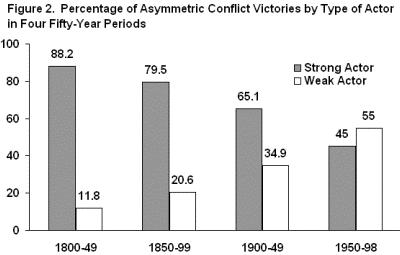

Second, on the issue of asymmetric conflict, the trend over the last two centuries is toward small powers defeating larger ones, to the point where in the latter half of the Twentieth Century, small powers actually defeat large powers more often than not. Below is figure 2 from Ivan Arreguín-Toft, “How the Weak Win Wars: A Theory of Asymmetric Conlict,” (International Security, vol. 26, no. 1, Summer 2001, pp. 93–128).

Given these two trends, the deck was stacked against the U.S., even with the greatest effort, but since it was undertaken by the Solomon Grundy administration (Wikipedia | Sean Baby) we never stood a chance. They know how to smash and that’s about it.

Neither of these two observations are new: both trends were generally known at the time of the invasion of Iraq — Ms. Walter’s book is from 2002 and Mr. Arreguín-Toft’s article is from 2001 and neither were breaking new ground. Five year on, it is now completely apparent outside of administration propagandists that the key strategic judgment with respect to Iraq was not how many soldiers in the initial invasion, or how many in the subsequent occupation, or whether to intervene in the looting, or to disband the Iraqi army, or seasoned experts versus right-wing sycophants to staff the CPA, or any of the many, many other mistakes, but whether to go into Iraq or not in the first place. Barring sufficient historical awareness here, at least the administration should have known and acted like the odds were not in favor of success. Instead we got the fast-talker’s sales pitch.

And as the Dolchstoßlegende crowd now attempts to rewrite the history of the Iraq debacle a la the Vietnam War version thereof, it should be born in mind that that war was part and parcel of these trends.