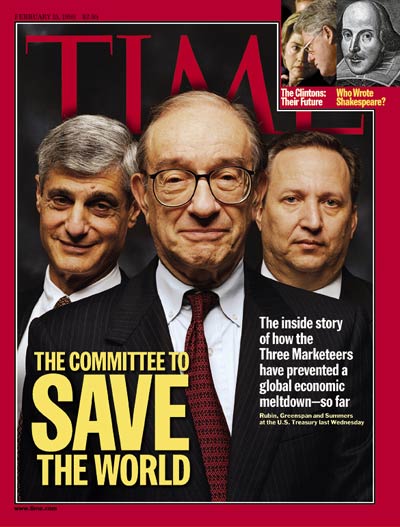

It’s mostly consigned to the past, but it increasingly seems to me that the Asian financial crisis of 1997-98 and the attendant reaction of U.S. economic policy makers was the watershed economic event of the present era. The economic handlers of the time, most outstandingly Alan Greenspan, Robert Rubin and Lawrence Summers came as close to the rank of heros as economic policy makers are allowed (“the committee to save the world” in Time Magazine’s famous formulation). During the period 2 July 1997 through 23 September 1998 — the floating of the Thai baht to the deal to bail out Long Term Capitol Management — the Federal Reserve held rates steady at 5.5 percent, then in September, October and November made a succession of impressively restrained off-committee 25 basis point rate cuts. The firebreak held and the U.S. economy got another 24 months of economic growth, crossing the line to become the longest uninterrupted economic expansion in U.S. history in February of 2000. On such a basis is the formidable reputation of Alan Greenspan built.

But the unenunciated strategy of Greenspan, et. al. during this period was to stave off the spreading crisis by converting the vast and voracious American body of consumers into the buyer of last resort for the world. The countries in crisis would be propped up through IMF aid packages, but also through the newly enhanced competitiveness of their goods on the U.S. market. This was accomplished through the aforementioned interest rate cuts, but also at Treasury through the strong dollar policy.

Source: Wikipedia; U.S. Census Bureau, Foreign Trade Division

The broadest mechanism by which interest rates work is through home mortgages. As interest rates decline they set off a wave of home loan refinancing, liberating spending previously sunk into housing costs. That combined with the (psychological) wealth effect of the stock market and a historic credit binge came together in the person of the American consumer to pull the world back from the brink. A glance at the above graph of the trade deficit shows that 1997 was the inflection point.

In so far as the way that the U.S. opted to combat the global spread of the anticipated “Asian contagion” was to transform the U.S. consumer into the buyer of last resort through loose credit, the collapse of the housing market bubble is the continuation of, or the knock-on effects of the Asian financial crisis of 1997-98. It could only be postponed, not avoided; transformed, not stopped. Old wine in new bottles.

It was fairly apparent to most observers during the late 1990s and 2000s that the Federal Reserve was struggling to stave off a crisis and did the best that it could, but was merely kicking the can down the road. There was plenty of commentary at the time that the Fed was merely letting pressure off one bubble by inflating another. And inside the Fed they were fully aware that this was what they were doing, but they had to deal with the crisis at hand and figured that they would cross the bridge of the iatrogenic consequences of their policies when they came to them.

In this sense the ultimate cause of the present economic crisis is a structural imbalance in the world economy that has a tendency to generate crises. One portion of the world, the developing, produces without consuming and as a result experiences a glut of savings. The other, the U.S., consumes by borrowing the surplus savings of that other portion of the world. Witness the current account deficit of the United States with China and the strategic fallout thereof. The problem is political-economic in nature and the ultimate solution lies in the realm of politics, not behind the scenes financial wizardry.